Or, What Happens When a Violinist Takes a Science Class

Kinesiology was the most rewarding class I took last semester.

For one thing, I never expected to find myself, a musician and not a sporty person, in a room full of future athletic trainers, PTs and chiropractors, who were on sports teams and lifted regularly in the gym.

At first, I felt like a fish out of water, but then my classmates inspired me and I started lifting weights, taking note of nutrition and running!

For another – the class was hard. We had to learn all of the muscles primary responsible for movement in the body, their origin and insertion points, what they do, and what other muscles they worked with. That, in addition to learning the basics of how muscles work and are structured, meant that I, who’d had mostly music history, theory and orchestra classes in my college career and little hard science, was more than a little daunted.

I’ve never been prouder of a B+.

The biggest personal win?

A couple classmates asked me to help them analyze the downstroke on the violin for our big class project, the movement analysis project.

The movement analysis project entailed finding a specific, specialized movement that a professional does – a basketball dunk, volleyball jump, football throw, etc. – and analyzing which muscles do the movement and how. We were to compare a professional doing the movement to an amateur to discuss the efficiency of the muscles recruited in the movement. Then, we were to present on common injuries resulting from the action and how to train to avoid such injuries.

Now, I’ve been injured 3 times playing the violin. That experience with injury led me to being an advocate for musicians’ health and future health educator. (That’s a whole other story that you’ll see on here, if I haven’t already talked your ear off about this in person!) This Kinesiology project got me really, really excited. I could finally analyze playing the violin from a scientific perspective, present on musicians’ injuries and actually know what I was talking about!!!

I wanted to include this project on the blog because it was an excellent introduction to movement education for violinists. Many musicians are not educated in basic anatomy and physiology applied to their instrument, which increases their risk of injury. A basic primer on movement education applied to the violin is invaluable for a violin student of any skill level.

What follows below is the result of my classmates and I applying our knowledge of the shoulder joint, an entire semester of Kinesiology education and our professor’s can-do attitude (he was the “amateur” performer of the violin downstroke – thanks Dr. K.).

Part I. Analyzing the Muscles Used

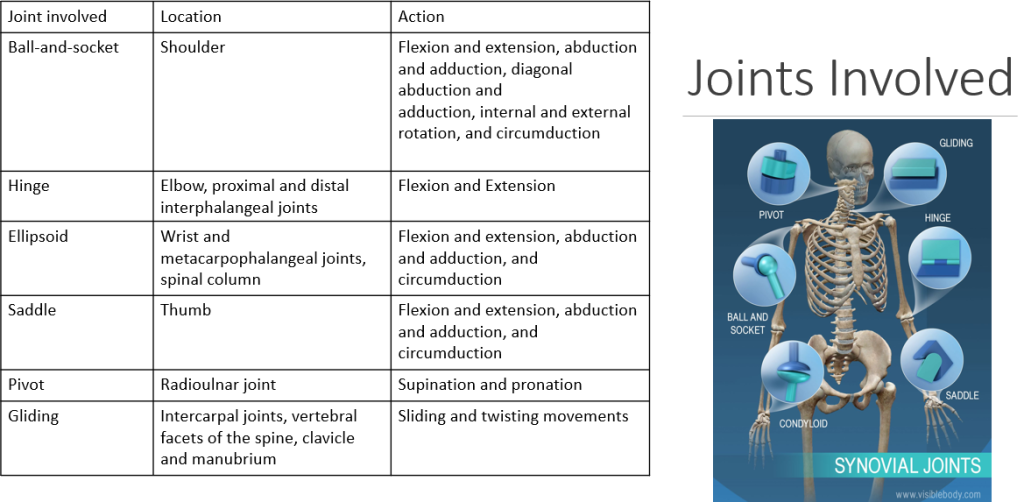

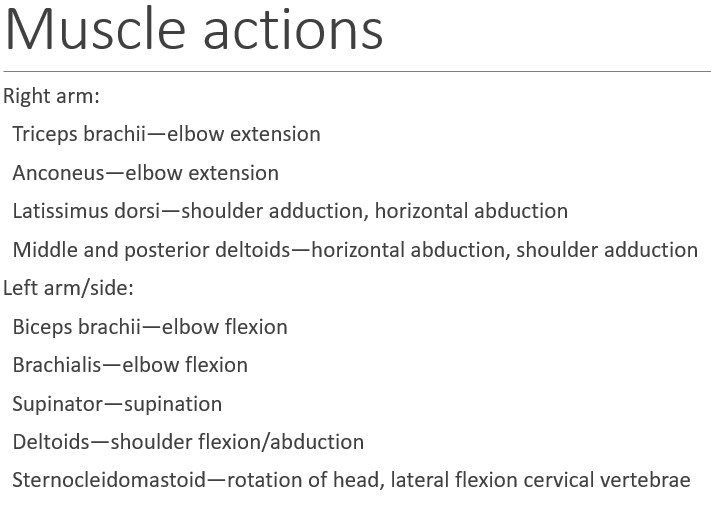

We began with describing the kinds of joints involved in playing the violin, their locations and what they do. Violin playing uses every type of joint: ball-and-socket, hinge, ellipsoid, saddle, pivot and gliding joints, and all of these joints are located in the upper extremities and axillary skeleton (shoulder, elbow, wrist, spinal column, thumb, radioulnar joint, clavicle and manubrium and the joints inside your hand and fingers). Most of these joints flexed or extended, but many of them were also responsible for sliding and twisting movements, supination and pronation, abduction and adduction, rotation and circumduction.

This knowledge was an important baseline to begin our presentation with, since it would lead to an understanding of how the joints worked together to accomplish moving the bow effectively and spots of likely injury.

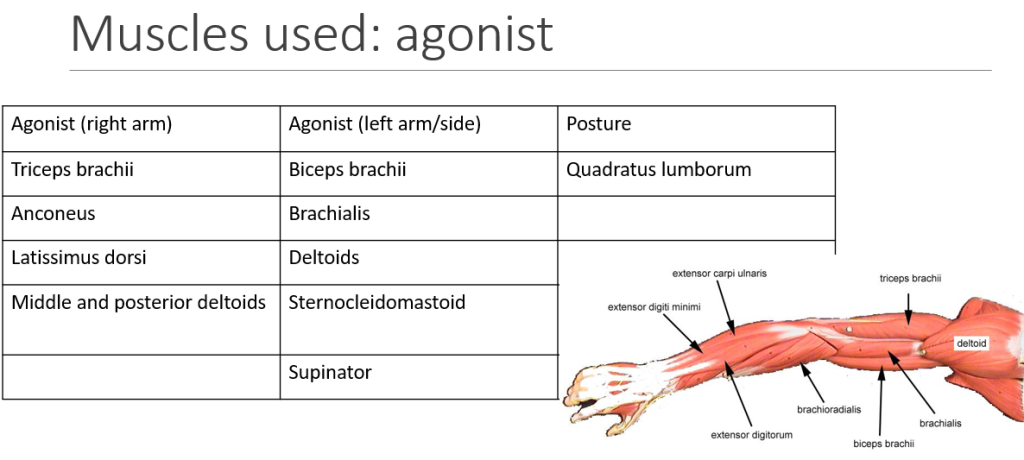

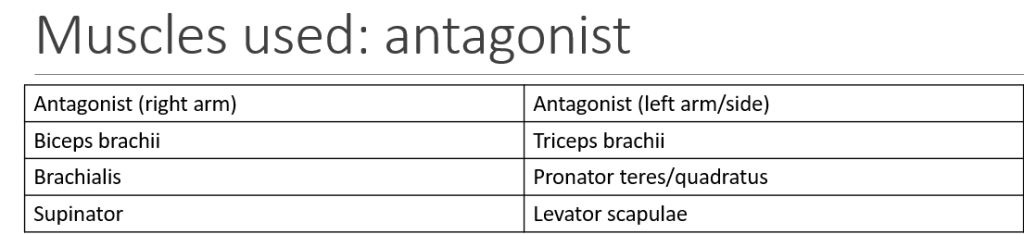

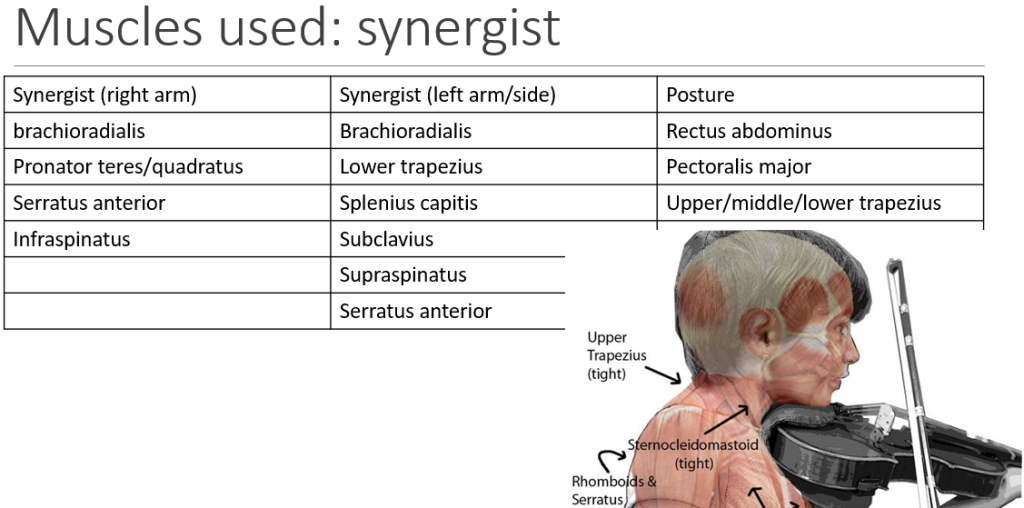

We then dissected which muscles would be used as primary movers (agonists), inhibitors (antagonists) and helpers (synergists). Essentially, agonist muscles would be the main muscle contracting to perform the movement, and antagonist muscles would relax to allow the agonist to work. Synergists help the agonists contract.

Analyzing these muscle duties gave us clarity on what specific areas of the body were responsible for each component of the playing action. For example, it would not be helpful to strengthen the triceps brachii on the left side to optimize performance, since it was an antagonist on the left arm. However, it would be very helpful to train and stretch the triceps on the right side, since it is an agonist on that side.

Part II. Analyzing the Movement

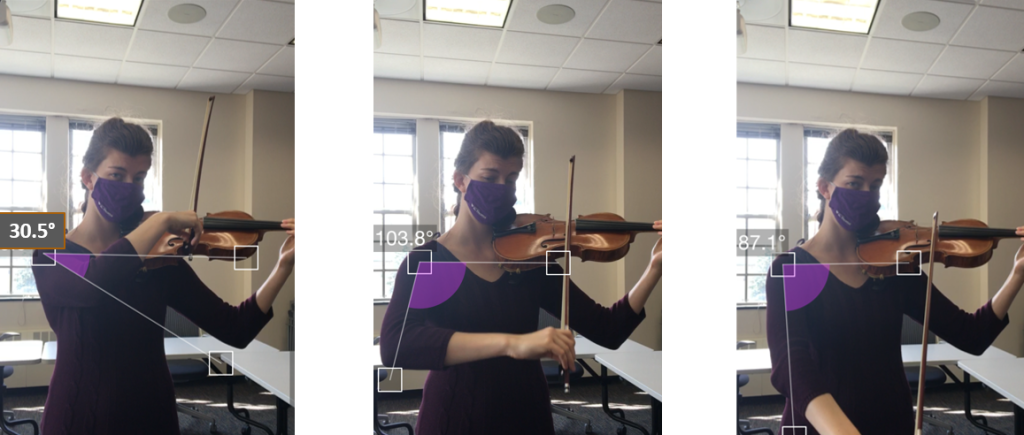

We compared my performance of a down stroke to an amateur’s performance who had just learned the movement that day to get an idea of ranges of motion for each muscle and compare planes of motion and movement directions. We found that my performance used the muscles more effectively, and as a result achieved better range of motion and used less energy. In general, we realized that using muscles effectively resulted in better performance and injury prevention, proving that movement education works!

Part III. Proposing Changes for Improved Performance

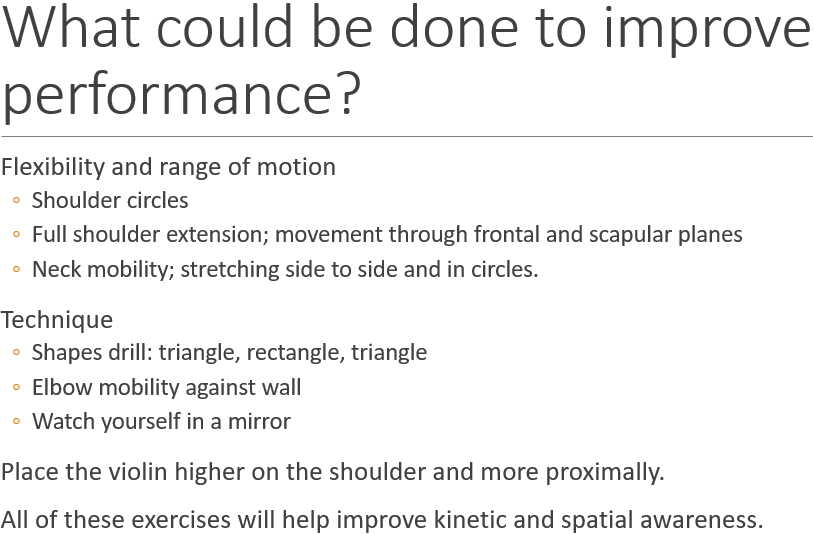

Our goal with our project was not only to gain baseline knowledge about how the body executed the set of movements in violin playing, but to apply that knowledge to performance and injury prevention. We determined that improving the player’s flexibility and range of motion in the shoulder and neck through multiple planes would encourage the efficiency of the agonist muscles. For example, moving the arm in front the player, behind, to the side and diagonally to the chest would encourage full mobility in the shoulder joint.

We discussed technique approaches to the bow that would improve performance, the most efficient placement for the violin, and finally, discussed improving spatial and kinetic awareness (a part of movement education essential for athletes and musicians of all types).

Part IV. Likely Spots of Injury

Unsurprisingly, I took the lead in this section since I had direct experience with it! I discussed where and how injuries were likely to occur.

The shoulder is one of the most mobile joints in the body (it and the hip are ball and socket joints, and since the shoulder has a shallow socket, it must be held in place by soft tissue – very injury prone). Because of this, injuries would likely occur at the shoulder joint. However, because musicians have a highly specialized movement practice that requires minute and extensive training, all of their joints are at higher risk than the general population for repetitive stress injuries. This is why focusing on movement education in lessons and practice is so important.

Musicians commonly suffer slow-onset injuries like tendinitis, bursitis, strain, nerve compression syndromes (carpal tunnel, thoracic outlet syndrome) and osteoarthritis. The gradual nature of these injuries make them difficult to catch early, which leads to a more severe injury and longer recovery. Musicians often have muscle imbalances contributing to their injury or injury risk, and their joints bear a great amount of force due to holding up their instrument (see here, here and here for some excellent explanations of torque and how this impacts the load muscles bear).

Part V. Injury Prevention

We kept our comments on this portion fairly general (none of us are health professionals! If you’re reading this and you’re hurt please seek medical advice for rehabbing your injury). Unfortunately, many musicians are not educated at all about how to take care of their bodies or that they should do so. Stigma around injury, personal beliefs, lack of movement education and bad practice habits contribute to musicians’ ignorance of their bodies and prevent them from getting help that they need.

Briefly discussing these factors led into our discussion of injury prevention with some common-sense tips (to athletes – not so much to musicians!): warming up, cooling down, stretching, avoiding playing through pain and seeing a doctor when you have recurring pain.

We also presented some prevention-oriented training methods: musicians need to do more endurance-based training, posture training and strengthening the small muscles that are necessary for their joints’ stability. We discussed preventing winging of the shoulder (muscle imbalance pulling the scapula [shoulder blade] out of alignment with the back and sides) and incorporating efficient technique to support health.

Part VI. Resistance Training and Stretching

This part of the presentation involved going through specific strength, conditioning and stretching methods for each muscle group involved in playing the violin. Many of the training ideas we presented are related to weight training and involve fairly typical stretches.

If you made it this far, CONGRATULATIONS!!! You made it through our movement analysis! Be proud – there’s a lot of information in this post. If you found it interesting or helpful, please consider sharing with friends, family and the string players in your life!

Many thanks to Dr. K, Holly, Emma, and Maria for collaborating on this presentation. You are fabulous and it was a pleasure to do research with you.